The Problem with Army Battle Drills

This short article is adapted from our new Squad-Level Infantry Rural Combat book and online certification course. The article discusses some critical drawbacks in the way the U.S. Army teaches battle drills to small units. We welcome your reactions, comments and ideas on our Facebook page and if you like the article, click below to check out the book on Amazon or enroll in the online course.

The Problem with Army Flanking Battle Drills

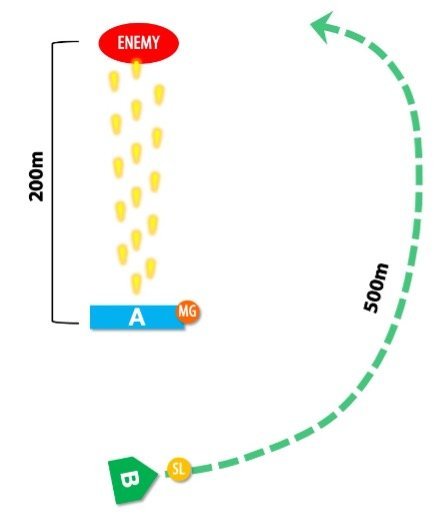

In our Squad-Level Infantry Rural Combat manual we explain the logic behind U.S. Army battle drills and discuss how many Army leaders misunderstand the nature of battle drills and how they are supposed to be employed. However, we also argue that this misunderstanding comes from flaws in the way that the Army explains and teaches battle drills in doctrinal manuals and schools. We then go on to point out several problems with battle drills the way they are typically executed by Army units. This article will cover those arguments. However, for sake of space, we assume readers are already familiar with the standard “suppress and flank” battle drill. For those who are not, refer to the diagram below. In general terms the suppress and flank battle drill involves one element (A) laying down suppressive fire while a second element (B) moves around to the right or left in a wide, bold flank to attack the enemy unexpectedly from the side.

PROBLEM 1: Engagement Distance and Ammo Load

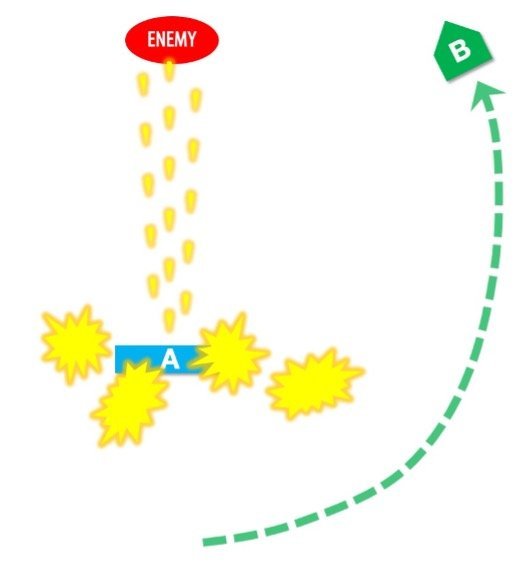

While the standard suppress and flank battle drill is intended only as a guideline or starting point for tactical maneuver, there are a number of problems with using the unmodified battle drill exactly as prescribed in the Army manual. The first has to do with the length of the flank. A typical engagement range in conventional warfare could be as far as 200m or 300m. This means if the flanking element makes even a moderately bold flank (as shown in the picture, the total movement distance for the flanking element will likely be farther than 500m. Moving 500m over rough terrain in full gear, especially at night can take time. Then consider that if the machine guns in the support position are firing at a sustained rate of fire, based on standard U.S. Army basic ammo loadouts, the light machine guns will have probably expended their ammunition and the medium machine guns will be at least half-empty by the time the assault element is in position to assault. These figures cannot be exact since many variables come into play, however, with the weapons and ammo available to the squad, a long, bold flank will likely present problems.

PROBLEM 2: Exposure to New Threats and Isolation

Given the engagement distances just discussed, by the time the flanking element is approaching the assault position, it will be able to see a lot farther and a lot more than the area originally visible to the support element. In the example below with shaded observation areas, the lead team understandably makes contact near the limit of its observation range and will see only one enemy element. As the trail team flanks around and moves ahead, it may see and be exposed to additional enemy elements that are not visible to the support element. The support element therefore cannot provide covering fire to help protect the flanking element. Furthermore, given that the flanking element is attempting a bold flank, the flanking element might be so far away that it is not even be visible to the support element when these new enemy forces appear. This could leave the flanking element completely isolated and facing potentially superior forces. At this point the two elements are no longer mutually supporting and therefore cannot effectively break contact.

PROBLEM 3: Unpredictable Enemy Reaction

The basic battle drill formula also assumes that the enemy either chooses to do nothing or is unable to do anything because they are completely suppressed by supporting fires. While either of these results is possible, it would be foolish to assume that the enemy will do nothing in every case. Combined with the possibility mentioned earlier of additional enemy units further away that you didn’t initially spot, there are quite a few possibilities for enemy counteraction. The enemy might attempt to flank you from the same side or the opposite side of your flanking element. The enemy might attempt to attack and destroy your support element or anticipate your flank and wait in ambush for your assault element. Even more likely, the enemy will simply try to pull back and break contact. Any of these actions changes the scenario and makes the basic battle drill formula break down in some way.

PROBLEM 4: Enemy Indirect Fire

As already discussed, depending on the engagement range it can take the assault element a while to bound around into the assault position. If the enemy has indirect fire assets like mortars or artillery, he will likely call in a fire mission as soon as the engagement starts. You should study patterns for enemy artillery employment and response time in your area of operations to know the approximate time window you have before rounds start falling on your position. If the enemy response time is fast, it might not be safe or wise to leave a supporting element in place for a long period of time.

PROBLEM 5: Attacks from Other Directions

Battle drills as explained in doctrinal manuals can be applied to enemy contact in any direction. However, because the specific examples, drawings and steps in the manuals often focus on contact to the front, military units frequently end up practicing only attacks to the front and fail to practice executing the battle drill in different directions. While the fundamental steps and movements of the drill remain generally the same, there are some important changes in how you execute the drill based on the direction from which the attack is coming. Taking a more flexible approach to fire and maneuver from the outset sets you up for success when encountering enemies from different directions.

We hope you found the short article useful and once again we welcome your reactions, comments or suggestions on our Facebook page where we frequently hold constructive discussions on tactics with people from various tactical backgrounds and experience levels. Also, click above if you would like to check out the full book on Amazon or enroll in the online certification course.